Category Archives: Fall 2013

Dialogues on Feminism and Technology

The experimental online class Dialogues on Feminism and Technology led by Anne Balsamo and Alexandra Juhasz has begun posting weekly video conversations. Sixteen colleges are participating, including CUNY’s Graduate Center and Macaulay Honors College, as well as thousands of learners outside of formal educational settings. The class is intended to be a model for open access pedagogy in a collaborative environment, in contrast to MOOC-style learning. For those without institutional logins, there are suggested readings to accompany the class.

As an example of the ideas about women and technology in popular culture that they are seeking to counter, class organizers point to a June 2012, New York Times article about Silicon Valley which opened with “Men invented the Internet.” Partly to address that type of thinking, students will participate in Storming Wikipedia, an exercise in writing and editing to include women and feminist scholarship in Wikipedia. HASTAC has a wiki page about the Wikistorming that took place earlier this year.

9/23/13 Cultural analytics: A guest lecture by Lev Manovich

Lev Manovich—a Computer Science professor and practitioner at the Grad Center who writes extensively on new media theory—delivered a guest lecture on visualization and its role in cultural analytics and computing on 9/23.

Basing his discussion on a range of visualization examples from the last decade or so, Lev highlighted how the rapid emergence of tools for collecting data and writing software have allowed artists, social scientists and others to investigate and question:

- the role of algorithms in determining how technology mediates our cultural and social experiences,

- how to work with very large datasets to identify social and cultural patterns worth exploring,

- the role of aesthetics and interpretation in data visualization projects,

- and how visualization projects can put forth reusable tools and software for working with cultural artifacts.

He also discussed previous and future projects undertaken by his lab, which developed at the University of California San Diego, and is now migrating to the CUNY Graduate Center.

Class discussion following the lecture highlighted the value of transparency in Lev’s work and processes—a value he affirmed has always defined his own publishing philosophy, even before he began writing software.

Another line of inquiry was based on how machines can be programmed to automatically “understand” content. A current challenge lies in developing computational methods that can make meaningful assessments of complex, contextualized objects. For instance, how do we train machines to go beyond simply recording strings of characters or groups of pixels (the kinds of data computers are fundamentally good at collecting), and instead write programs that have the potential to generate insights about types of sentences or faces? What is the role of visualization in meeting this challenge and how is it different than other scientific methods, like applying statistics to big data?

privacy and recording lectures

Like Sarah, I take for granted that public universities and classes promote information sharing. The articles and cases I’ve read are very blurry–according to NY Recording law, recording in a public university may fall under the category of recording a public meeting…which means no consent is required.

This article raised some great points, focused on Livescribe recordings.

Here is the direct link to NY’s recording laws.

DefiningDH

Initial:

The digital humanities is an academic community, its members united by interest in (and use of) digital tools to 1) redefine their research and analytical practices and/or 2) cultivate new forms of academic collaboration and dialogue. Its sustainability, emergent goals, and politics are reactive to wider industry developments and economic forces.

Secondary:

The Digital Humanities is an emerging discipline within the field of information science.

Reflection:

I have found it exciting to follow DH issues and studies that are continually emerging in networked spaces, shaped by a dynamic community that seems to self-identify and develop new ideas at a rapid pace. Discovering the latest questions and critique within the discipline itself has piqued my interest in understanding the trajectories of those discussions. But while I think the world of DH-introspection enriches the discipline and fosters its growth, it at times seems a veil for the natural growth and potential for the field. Given the rapid adoption of digital tools, computational frameworks, and data mining in most areas of contemporary scholarship (and industry, government, etc.), I’m interested in why proving the value and relevance of digital methods within the humanities is a different process than it is in other realms.

As a result, I’d like to further explore how DH, as a practice, resonates with larger trends in digital practices, and how deeply interdisciplinary projects manifest the value of DH methodologies — perhaps in ways that transcend semantic qualms and curb the agency of an Analog vs. Digital duality.

But if DH is contingent on dualism (at least for the time being), perhaps alternative definitions of DH arise when one of its basic value propositions (that digital tools will deliver new value to the humanities) is inverted. For instance, there are computer and social scientists interested in questions of language, interpretation, expression, philosophy….so how can longstanding lines of inquiry in the humanities bring new dimensionality to the methods that those social and computational scientists use? I am hoping to come to a 3rd definition of DH that fortifies the idea (in practice as well as theory) that the digital needs the humanities just as the humanities need the digital.

Remediating the Avant-Garde

Just wanted to let everyone know about a two-day program at Princeton University in October on Avant-Garde magazines and digital archives. Looks to be a fascinating discussion on how to represent these periodicals in a digital landscape — and the program is free.

More info here: http://bluemountain.princeton.edu/conference/index.html

Defining DH

Before our class conversation, I defined Digital Humanities as the practice of accessing and exchanging ideas and scholarship through interconnected digital platforms. I understood the Digital Humanities as the field which merges scholarship across the wide spectrum of academic disciplines with modern technological advances to realize ideas through a more effective and relevant context.

Following our discussion, I would redefine Digital Humanities as a practice of accessing, developing, communicating, and exchanging ideas and scholarship through digitized mediums. I still hold that the field aims to fuse modern scholarship with modern technological capabilities in order to produce relevant, effective idea exchange. This growing field realizes that in our digitizing world, the individual’s capacity for thought and creation is heightened. In order to advance our ideas and scholarship in this changing context, we must utilize digital mediums. The Digital Humanities guides this adaptation.

Defining the digital humanities

Prior to class: The digital humanities examine social and cultural objects/phenomena that are the result of a collusion with digital technologies. Digital humanities examine digital space and concepts in the human disciplines.

After class: The digital humanities encompass a range of tools for analysis, instruction, and pedagogy that incorporate digital techniques to address questions in the humanities.

To me, there is a big difference between digital technologies (textual analysis, GIS, etc.) and studying the ways technology interacts with other fields of study. In the readings, I was particularly drawn to the concept of “eversion,” that cyberspace and physical space are deeply interwoven. I agree with Nathan Jurgenson’s argument about the queering of the on- and offline; though the digital and physical are not one perfect unity, the distinction between the categories has become increasingly destabilized. The idea that there is a separate “offline” is no longer valid.

Going forward in the course, I would like to better understand how the two definitions I stated above work in tandem: how can digital technologies and tools also be understood as a critical component of the humanities?

The Science/Humanities Gap

A few of the DefiningDH blogs have touched on the disparity between/problem of digital research methods in the sciences and humanities, and how humanists can use technology in their work. Here is a recent NY Times article I stumbled across on this:

http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/09/18/sciences-humanities-gap/?_r=0

Without mentioning Digital Humanities per se, the author (who is responding to another interesting article about how humanists MUST embrace the sciences) believes humanists are well aware of this gap:

Pinker notes the antiscientific tendencies of what he calls “the disaster of postmodernism, with its defiant obscurantism, dogmatic relativism, and suffocating political correctness.” But literary studies, the bastion of these tendencies, have long been moving in other directions, including a strong trend toward applying scientific ideas and methods. There is, for example, the evolutionary and neurological study of literature and, most recently, the use of computer data-mining.

There is, then good reason to think that the greater problem is scientists’ failure to attend to what’s going on in the humanities.

In the readings this week, Lev Manovich poses a similar problem in relation to data access and interpretation:

I have no doubt that eventually we will see many more humanities and social science researchers who will be equally as good at implementing the latest data analysis algorithms themselves, without relying on computer scientists, as they are at formulating abstract theoretical arguments. However, this requires a big change in how students in humanities are being educated.

Manovich leaves this question open-ended, and it’s a big one. Both authors seem to be bothered by disciplinary narrowness and a lack of cooperation across disciplines.

I don’t know about anyone else, but part of the reason I was attracted to Digital Humanities was the fact that many of my research and teaching questions can’t be answered by taking more Literature classes.

Like the MTA — Improving non-stop!*

During class, I suggested that digital humanities was the digital creation and recreation of artifacts in order to reach the widest audience possible.

After listening to how others defined DH and reflection upon the reading, the field of digital humanities seems a bit harder to define. Since 3D printers can create physical objects, I think my focus on digital artifacts is perhaps too limiting. This time around I would also want to incorporate digital scholarship and pedagogy. Perhaps something more like: the incorporation of digital tools to create artifacts and methods that transform scholarly communication and pedagogical practices. That’s certainly a mouthful!

If I had to give certain attributes to the field of digital humanities I would say that it’s open in process and product as well as collaborative and disruptive in nature. I am involved in the ePortfolio project on my campus and trying to define dh reminds me in many ways of trying to define eportfolios. Of course, one could simply say that an eportfolio is a digital portfolio, but I would argue that it’s much more than that. I see it as a way for instructors to highlight (and perhaps recalibrate) high impact practices while giving students a sense of authorship and ownership.

In class I was struck by the number of students who expressed concern over privacy and sharing because it just seemed like a natural thing to me. Having graduated from one of CUNY’s online degree programs at SPS (and now administering their ePortfolio project) I guess I’m a bit more comfortable with the idea of sharing my work as well as the concept of peer review. After reading more about the history of peoples’ reactions to technology and it’s power to transform in my ITP Core 1 class, to question technology seems like a natural human response.

While I enjoyed all of the readings for class this week, Susan Hockey’s historical rundown of humanities computing and her focus on the importance of the TEI (Text Encoding Initiative) really spoke to me. The fact that these academics were able to collaborate and create guidelines which served as a model for those in the field seemed at the very heart of digital humanities.

I just want to end by saying that what drew me to the digital humanities track in the MALS program was the idea of making (which is why I’m totally bummed that I didn’t go to Maker Faire this weekend). Creating resources for students and faculty is one of the things that I love the most about my work with the ePortfolio project on my campus, and, since I need to make ePortfolio resources for students who may live in Hawaii, I enjoy the challenge of having to create things that are comprehensive yet easy-to-digest. The point is that it’s always changing and (hopefully) improving.

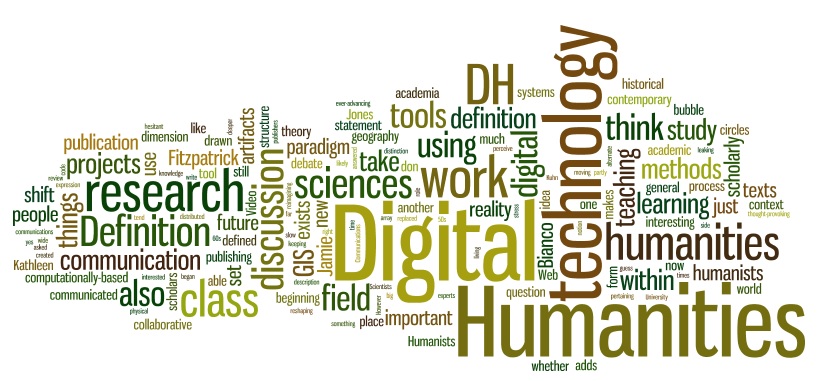

Since this week is about data visualization I decided to make a word cloud based on the #definingdh tag for this blog using wordle.net. Enjoy. 🙂

* I’m not the biggest fan of the MTA (as can be noted by my various MTA tweets), but I’m a sucker for a good slogan so there you go.